Building a Commitment to Safety

By Grainger Editorial Staff 7/1/19

OSHA also invites organizations to share and celebrate their successes with Safe + Sound Week each August. Visit OSHA’s website for activity ideas and more.

Safety programs tend to move from one trend to another. It's easy to see why. Trendy strategies—like the Safety Training Observation Program (STOP), Behavior-Based Safety (BBS) or People-Based Safety (PBS)—can be effective in achieving short-term injury reduction. But trend-chasing is not enough. For strategies like these to succeed in the long term, it takes commitment, too.

Commitment is when you walk the walk. It's what makes safety practices meaningful rather than mechanical. It's what inspires employees to contribute personally to workplace safety. Building a commitment to safety has been shown to significantly reduce injuries in the workplace. But it's easier said than done. This paper discusses two distinct approaches to the challenge of building and sustaining a commitment to workplace safety: People-Based Leadership (PBL) and Acceptance and Commitment Training (ACT).

Accident Statistics

In the past 50 years, there has been a steady increase in workplace safety awareness and a steady decrease in workplace fatalities and injuries. Since 1970, work-related fatalities have decreased more than 66 percent, and occupational injuries and illnesses have dropped 67 percent, according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). During that same period, the US workforce has nearly doubled.

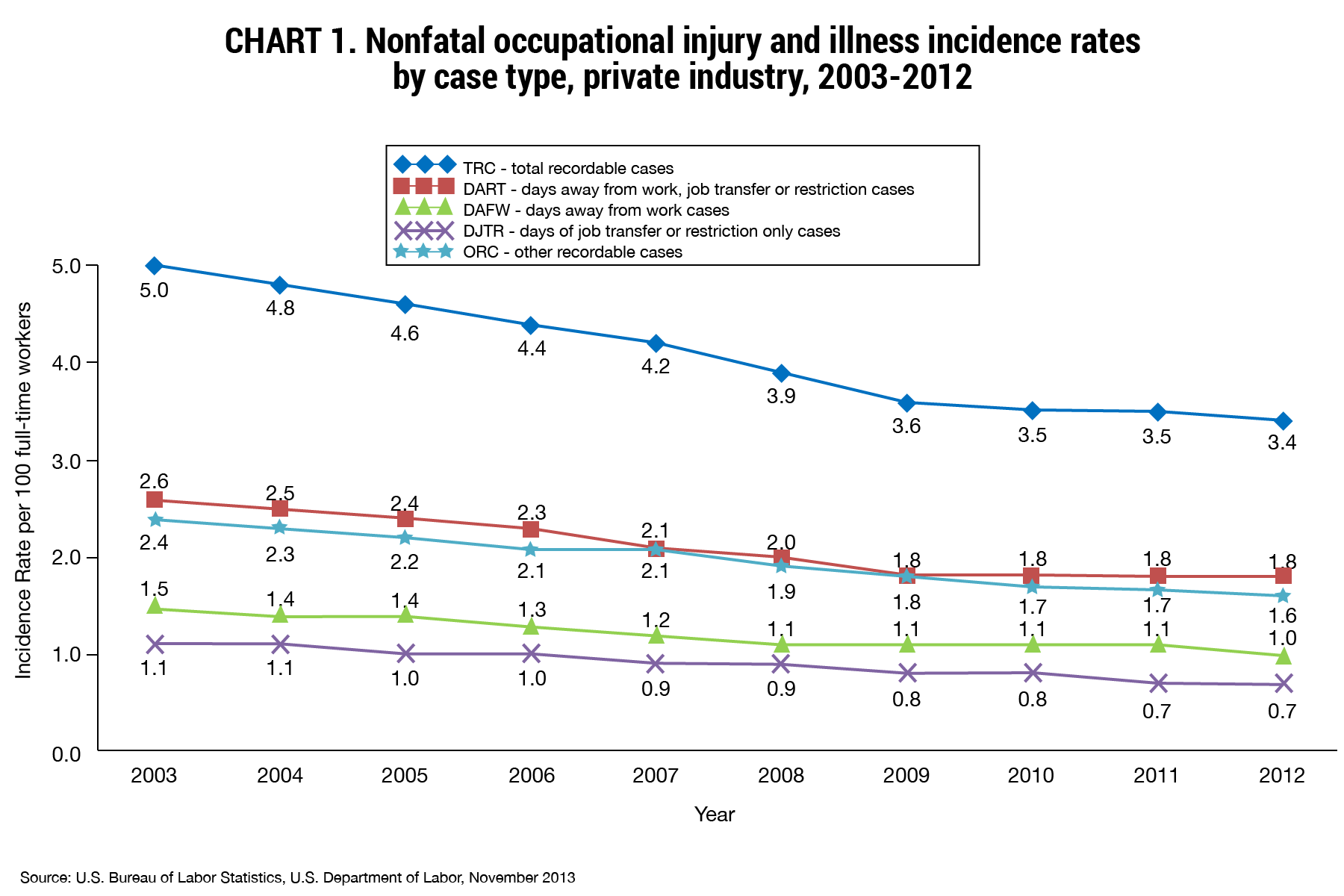

But despite this evident progress, the rate of improvement has slowed in recent years (see figure 1). The one essential ingredient that can sustain the downward trend in workplace fatalities and injuries is complete commitment to safety in the workplace.

Figure 1

Safety Culture

Creating a strong culture of safety in the workplace can be complicated and difficult. It requires a comprehensive approach that involves continuous improvement, generally around six components of safety: leadership, systems, behaviors, employee engagement, internal person factors, and conditions. It also takes commitment, which flows in part from the personal connections between an organization's leadership and its employees.

Away from work, friendships are deeper when they're built on hard-earned understanding, knowledge, and trust. Workplace relationships are the same way, and safety programs will be more effective when they go beyond the surface and reflect a deep understanding of what's truly important to the people in your organization.

Building and Sustaining Commitment in the Workplace

People-Based Leadership is an extension of Behavior-Based Safety, which has been found to significantly reduce industrial injuries. It was developed by Dr. Scott Geller, a professor at Virginia Tech University and director of the Center for Applied Behavior Systems. It's built around the insight that specific leadership principles and strategies can empower a workforce to become self-accountable for injury prevention and actively care for the safety and health of others. It uses evidence-based principles and procedures, formulated using objective, reliable data.

A PBL safety culture gives rise to four practices:

- Act to protect oneself and each other from unintentional injury

- Coach oneself and one another to identify barriers to safe acts and provide constructive feedback

- Think in ways that activate and support safety behavior, and focus and scan strategically

- See hazards and at-risk behaviors

PBL emphasizes leadership over management. Where a manager holds you accountable for acting, a leader inspires you to act. And leaders are usually the people who have the most influence on our lives—who motivate us and inspire us to higher achievement.

Dr. Geller identifies four strategies that foster leadership, rather than management:

- Listen. Leaders listen actively, hearing both good and bad news. They put aside their biases and pay attention to everything in a conversation. They listen with empathy by understanding or feeling what another person is experiencing before offering advice or direction. And they learn more by asking relevant questions.

- Emotion/empathy/empowerment. Leaders are enthusiastic and passionate, and they show respect and appreciation for the people they lead. Leaders understand the power of positive behavioral consequences, and are constantly searching for ways to reward and support desirable acts through emotion, empathy and empowerment. Leaders influence employees using personal stories that describe their own experience of similar situations, showing that they can relate.

- Accountability/authentic. Safety programs have traditionally focused on external accountability, but the long-term effectiveness of a program requires internal accountability, or self-motivation. Where external accountability is failure-focused, internal accountability also takes stock of positive accomplishments, like safety hazards removed, near-hit reports submitted and reviewed, or safety audits completed. These are proactive measures that seek to remove hazards before they lead to injuries or other events that are tallied in a traditional external accountability system. Authentic leaders are more interested in empowering the people they lead to make a difference than in accumulating power, money or prestige.

- Data. People can't improve without specific, data-based feedback. But the data must be carefully selected to identify accomplishments, not just accidents and other negative events. Be skeptical of opinions and recommendations, even if they make sense—always back them up with data that can be used to facilitate continuous improvement.

In a 2007 paper,* Dr. Geller summed up PBL this way:

“Safety management is necessary at times to hold people accountable for doing the right things for injury prevention. However, management alone is not sufficient to achieve and sustain an injury-free workplace. PBL is needed to build the kind of culture that inspires responsibility or personal accountability for safety.”

If you can inspire and make someone accountable, you will gain and sustain commitment to safety.

Acceptance and Commitment Training (ACT)

Another approach to building commitment to safety in the workplace is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Training (ACT). A leading proponent of ACT is Dr. Daniel Moran, the Senior Vice President of Quality Safety Edge. It draws on his 20 years of experience applying behavioral principles in clinical and business environments.

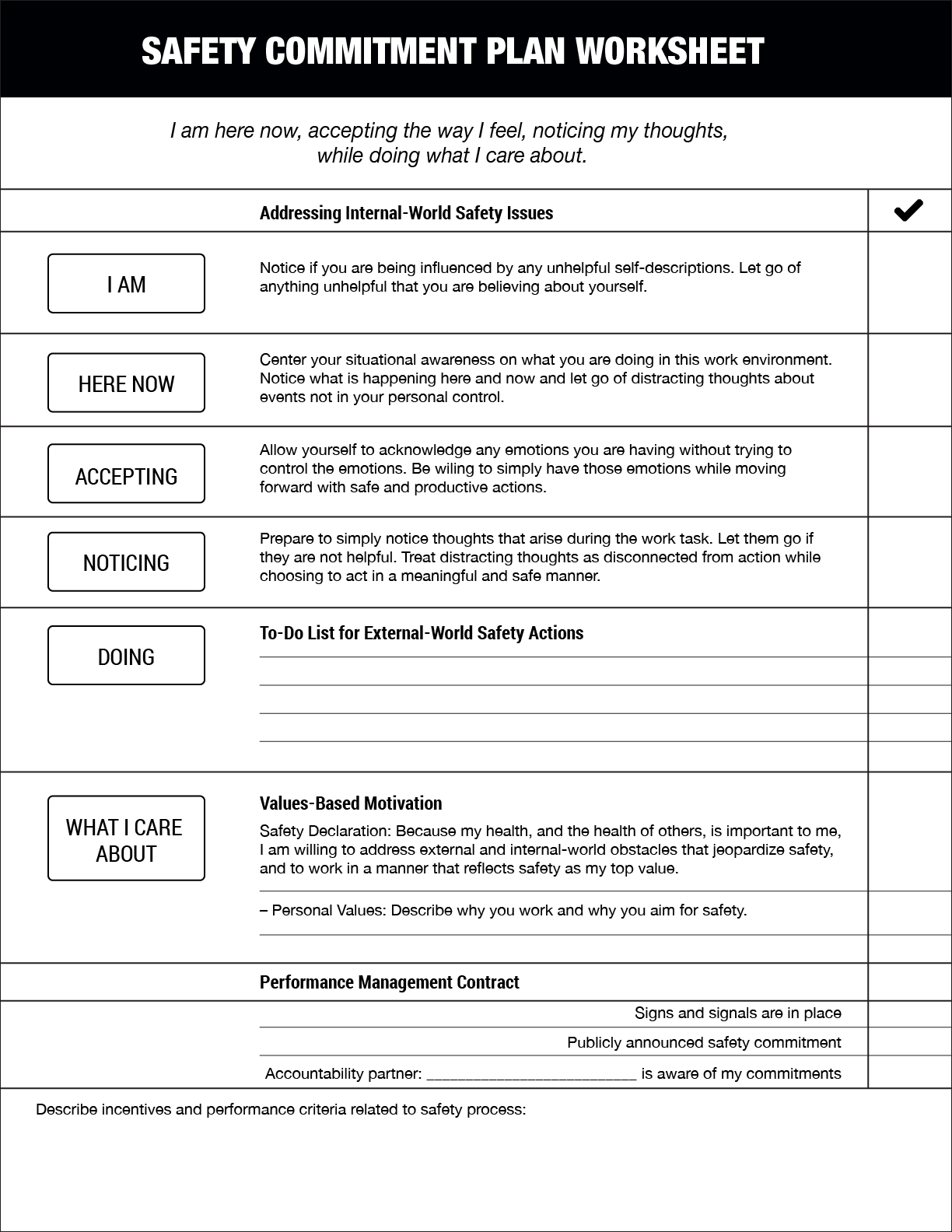

ACT is based on the set of interventions shown on the safety commitment plan worksheet in Figure 2. Using techniques informed by behavioral science, the interventions help workers build the situational awareness that allows them to focus on specific actions and move toward value-based consequences. In a 2015 paper,** Dr. Moran presented the central idea of ACT:

“I am here now accepting my emotions, noticing my thoughts while doing what I care about.”

This thought process is the outcome of mindfulness training, an approach that helps people make a solid commitment to safety. It's also a simplified definition of situational awareness.

Defined more completely, situational awareness is an understanding of what's happening around you—internally (in thoughts, emotions and sensations) or externally (sounds, moving objects, etc.)—that allows you to act appropriately. As an example, think of workplace ethics training, which is a way of building a very specific type of situational awareness. Ethics training helps employees recognize circumstances in which their own actions could tarnish their company's reputation. By recognizing these circumstances using situational awareness, employees can prepare themselves to act carefully and deliberately.

Similarly, when workers sharpen their situational awareness with respect to the internal and external stimuli that they experience on the job, they can recognize dangerous situations before injuries happen. According to Dr. Moran, this requires an ability to focus, refocus, and refocus again on what's going on in the environment in the present moment. ACT has been proven to sharpen focus and improve situational awareness so workers can follow through on their safety commitments.

Need for ACT

Like it or not, people are distracted in the workplace. One study concluded that we're distracted for 47% of the day while on the job.** To any safety professional, this spells trouble. If workers aren't focused, they can miss important cues to stay safe.

ACT addresses the problem of distraction by teaching situational awareness. When workers are trained to be mindful of their surroundings and to notice thoughts, emotions and sensations, they'll have tools that overcome distraction, which can help prevent injuries on the job.

ACT offers mindfulness training through six interventions that echo ACT's central idea—I am here now, accepting, noticing, and doing what I care about:

- I am—Thinking about your own identity and letting go of any unhelpful self-descriptions

- Here now—Centering your situational awareness on the task at hand, rather than things that are out of your control

- Accepting—Acknowledging your own feelings without trying to control them

- Noticing—Observing any thoughts that arise during work and letting go of those that are unhelpful

- Doing—Taking action to increase safety

- What I care about—Understanding why you work and why you care about safety

Figure 2

According to Dr. Moran, these interventions can help individuals commit to safety by strengthening the skills shown on the safety commitment plan worksheet (Figure 2). Through ACT, organizations can build safety commitment.

Conclusion

Everyone wants to be safe on the job—but creating a culture that's truly committed to safety can be difficult. Building that commitment can be difficult.

In this article, we've seen two contrasting approaches to that challenge: PBL, which emphasizes leadership as a means of instilling personal accountability, and ACT, which emphasizes mindfulness training as a way to increase the kind of situational awareness that prevents workplace injuries.

Although PBL and ACT represent two very different ways of building commitment to safety, both programs recognize the importance of values in the workplace. This is an important insight. Playing "safety cop" can yield short-term gains, but it will never lead to the creation of a strong safety culture. By forming deep connections with each other based on shared values, and by helping each other internalize safety-supporting values, we can build the commitment to safety that is so important for long-term success.

How Do You Talk About Safety Culture?

Grainger is rewriting the conversation in our new white paper, “How We Should Talk About Safety Culture.” This white paper gives safety leaders strategies to make real change.

Sources

* June 27, 2007, American Society of Safety Engineers (ASSE) proceedings Session Paper 507: "People-Based Leadership: Gaining and Sustaining Engagement in Occupational Safety"

The information contained in this article is intended for general information purposes only and is based on information available as of the initial date of publication. No representation is made that the information or references are complete or remain current. This article is not a substitute for review of current applicable government regulations, industry standards, or other standards specific to your business and/or activities and should not be construed as legal advice or opinion. Readers with specific questions should refer to the applicable standards or consult with an attorney.